Great (Fundraising) Expectations

By: Sean Maier, Senior Associate, WestRiver Group

This is the third of a three installment education series by WestRiver Senior Associate Sean Maier.

—-

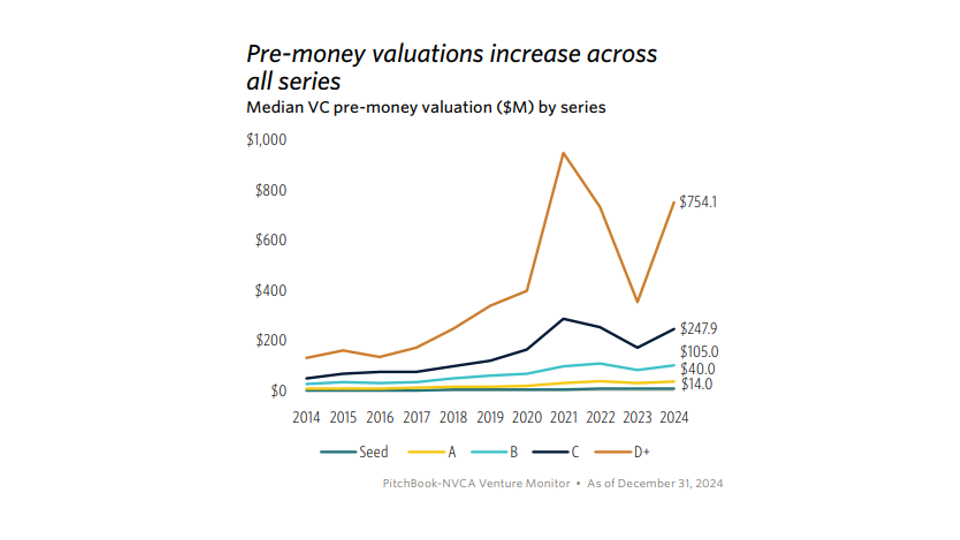

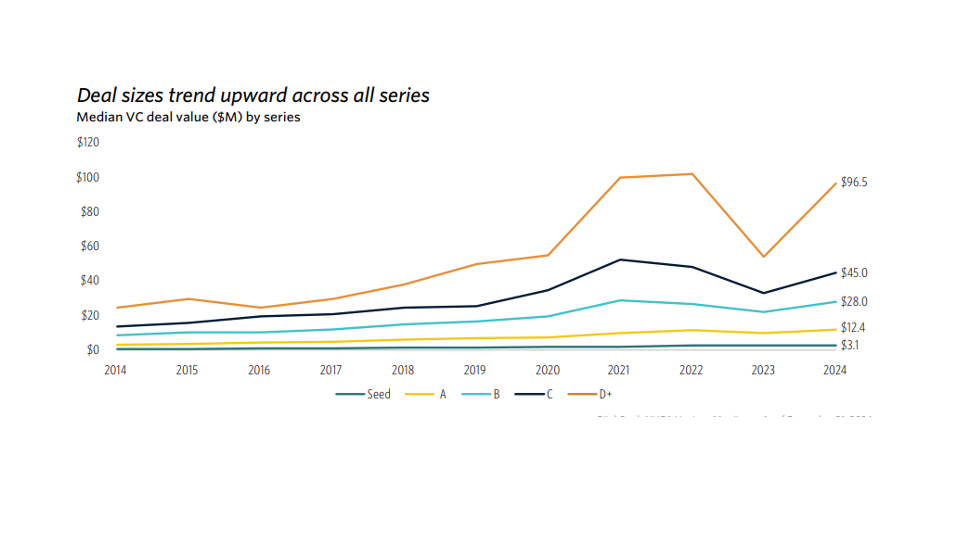

Pitchbook recently published its Q4 2024 venture monitor, which provided some insight into key trends in the venture ecosystem—among them, pre-money valuations and deal size. Notably, both have rebounded from a brief dip in 2023 and the overall trendline continues to remain “up and to the right”, as evidenced in the charts below.

A not-so-earth-shattering hypothesis is that this rebound is a reflection of fervent investor excitement about AI. The thing is though, looking at valuations and round sizes really only tells part of the story. What are investors’ expectations amidst investing more capital at a higher price?

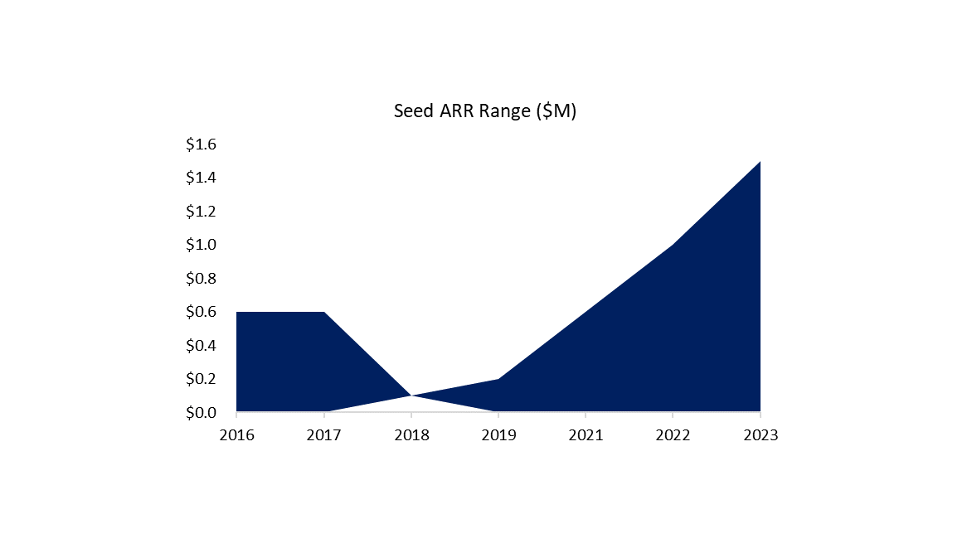

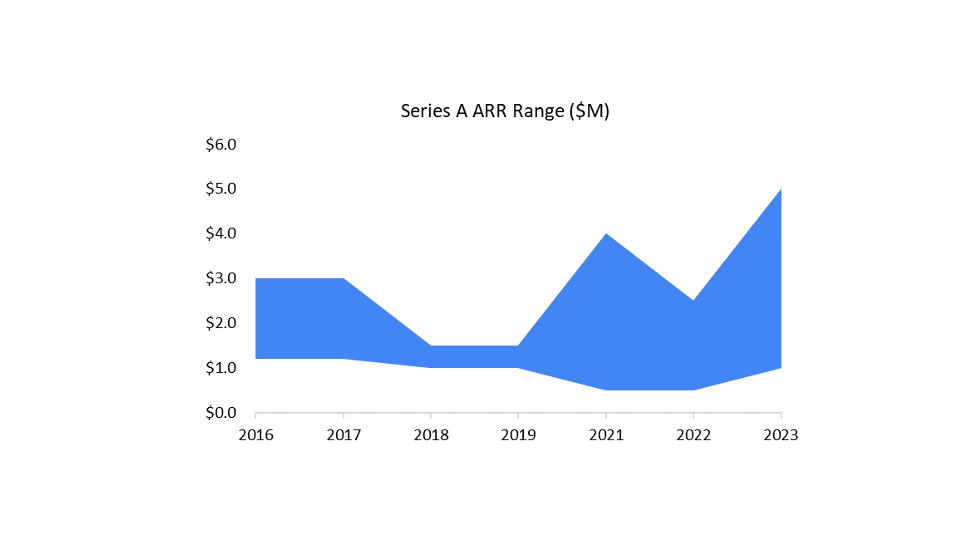

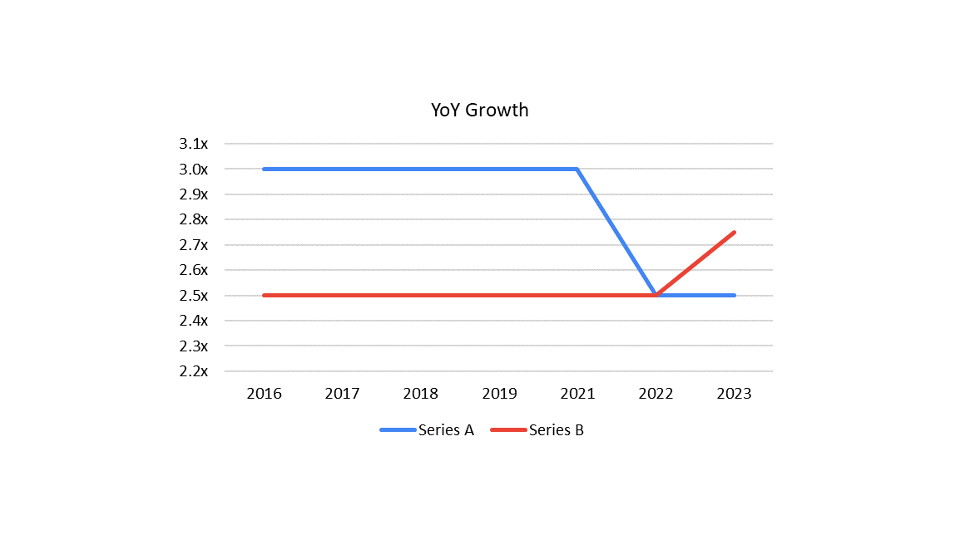

A logical place to look would be investor communicated benchmarks and “milestones” for different fundraising stages. Chistoph Janz at Point 9 Capital has published an annual “SaaS Napkin” every year since 2016, which summarizes the key metrics needed to raise capital at different funding stages. Christoph admits the napkin has always been a mix of art and science, and he did not publish one for 2024, but it should provide a reasonable sense of investor expectations.

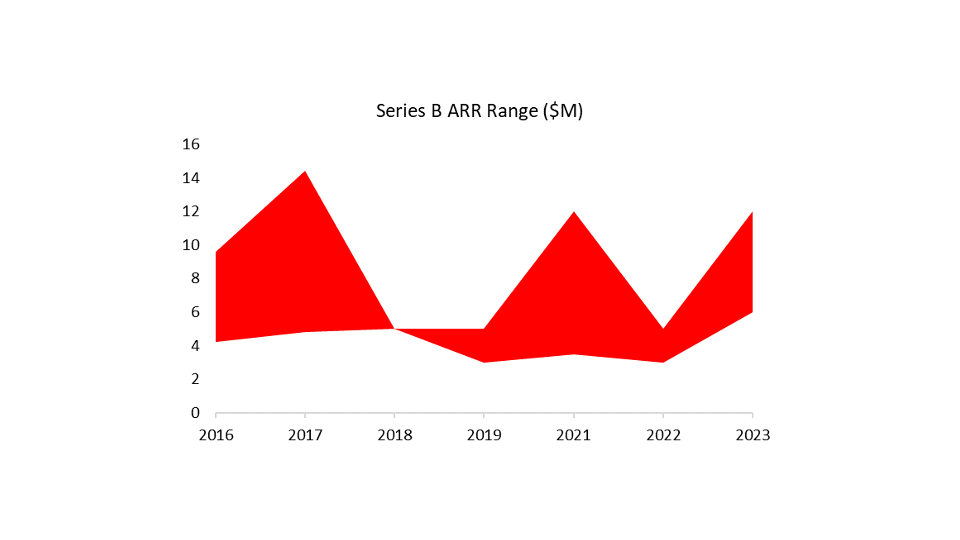

The ARR threshold for seed and A has remained pretty consistent over time while the ceiling has raised. Meanwhile, the band tightened for series B in 2023.

In his latest Napkin post Christoph, went on to say that one interpretation is that companies are waiting longer to raise and are thus further ahead than before—which startups will need to take into consideration vis-à-vis funding strategy, burn, and runway. This is somewhat supported by Wing’s latest V21 study, in which they analyze and report on the trends and characteristics of companies invested in by at least one of 21 “elite” venture capital firms, “V21”. Their findings show that the median number of years since founding and % of companies generating revenue has increased across the board since 2010. If you have time I encourage you to read the full report here. I would argue that this dataset is a better pairing for the SaaS napkin data than pitchbook’s, which is much broader and doesn’t break out series A or B.

After the excesses of 2020-2021, the 2022 and 2023 SaaS napkins (unsurprisingly) began including a capital efficiency metric— David Sacks’ burn multiple, which is net burn (I prefer to look at free cash flow) divided by net new ARR (new + expansion – churn). In other words, how much did you spend to achieve each new dollar of ARR. The most recent napkin from 2023 had burn multiples of <3-4x and <2x for series A and series B, respectively.

Wing’s report also includes a table with round size and valuation by funding stage over time:

Let’s apply the burn multiples from the SaaS napkin to the round sizes in 2019 (pre-covid) and 2023 for a post-Seed startup raising a Series A and a post-Series A startup raising a B, to calculate the implied net new ARR. For simplicity, we’ll assume that the entire round is burned on the path to the next fundraise (a number of companies raise additional capital between rounds, but let’s ignore that).

Seed raising Series A:

2019: $3.0M / 3-4x = $1.0M - $750K in net new ARR

2023: $5.2M / 3-4x = $1.3M - $1.7M in net new ARR

Series A raising Series B:

2019: $12.0M / 2x = $6.0M in net new ARR

2023: $17.2M / 2x = $8.6M in net new ARR

Generally speaking, if a company is raising much more capital than the median round size (Wing’s data showed 39% of the series A rounds tracked were $20M+ and 19% were $30M+), then the investors are either willing to tolerate a much higher burn multiple to reach the next milestone threshold (perhaps they’re building a deep technical moat), or they expect more growth. A word of caution.

A high burn multiple can be a red flag to the next round of potential investors while conversely, overzealous growth expectations can be an insidious thing for an early-stage startup that is still calibrating its product market fit. Further, a large fundraising round and valuation can often be erroneously conflated with already having product market fit, which couldn’t be less true and ends up leading to the aforementioned burn issue. Second, over-capitalized early-stage startups innately lack some of the constraints that force rapid iteration, focus, and testing central to finding product market fit. It takes a discipline to not put an entire round to work in 18-24 months, especially if some VCs have the expectation that should be to achieve the necessary level of growth. For startups raising venture capital, the question has been and always will be how much capital do you need to reach the next milestone.

Now, reaching these admittedly somewhat arbitrary milestones isn’t a guarantee that people will be lining up at the door for your next round— investors must believe there’s an opportunity for venture scale returns. Central to that will be evaluating the product, market, team, and business model along with the investment to date that went into reaching said milestones. The less time and capital needed, the better. Investors and founders should gameplan for their next milestones accordingly.